Almost 35 years ago, in Roanoke, Va., my post-college roommate Teresa and I used to make an allegedly Chinese dish whose recipe she had clipped from a newspaper. It consisted of shredded beef and cabbage, spaghetti and as much ground black pepper as we could stand. It was oddly delicious, though we always questioned whether it was authentically Chinese. It didn’t look like anything we had ever seen at Suzie Wong’s, the Chinese restaurant in State College, Pa.

This week I had it for lunch in Xiangtan.

At Will Long Cake, a bakery with a dining room attached (the Junior’s of Xiangtan? Its sign is the same orange), the waitress handed me a rare English menu, and the words jumped off the page: Beef Black Pepper Spaghetti. When my tray was delivered a few minutes later, the dish looked slightly different from the Roanoke version: it was more golden in color, and instead of cabbage, it had shredded carrots and red peppers. (In this town, every dish, even fried rice, comes with some form of red pepper — occasionally sweet pepper, as in this one, but more often slices of vibrantly colored, lethal little chilis, or dried pepper flakes.) The spaghetti looked and more like Western pasta than most of the noodles served here. But the slow-burn sensation that begins in the mouth and throat as soon as the nose detects the black pepper in the sauce is exactly what I remember.

Will Long may be the most upscale establishment on what I call Restaurant Row, just up the street and around the corner from my apartment. Restaurant Row couldn’t be more different from West 46th Street. It’s lined with open-front restaurants, many of which have their cooking done at carts out on the street. There’s the dim sum lady who puts hot sauce on my pot stickers without asking; the Muslim noodle place (no pork, and don’t bring in any alcohol); the grills where skewers of meat are cooked while you wait; the carts with little round casserole dishes piled high with greens, meats and mushrooms that cook down, over high heat, to garnish the soupy rice noodles on the bottom; and the king of them all, the fried rice man. I haven’t even had a chance to try the steamed buns on my corner for breakfast.

The fried rice man holds court in front of a charcoal burner with his wok, turning out one dish after another — fried rice, noodles on request, greens sauteed with garlic – to eat in the restaurant behind him or take away in small plastic-foam boxes. Another man, who acts as cashier, brings out a continuous supply of rice in stainless-steel bowls, and fresh greens upon request. The wok is smoking-hot, just as the eminent Chinese cooking authority Nina Simonds used to describe it when she wrote for me at The Boston Globe. The chef makes his work both and art and a science: a generous pour of oil, followed by an egg, followed by a coarse green mixture of spices I have yet to identify, then garlic, ginger, salt, those red pepper flakes and eventually the rice, which he turns and tosses for several minutes until he judges it hot enough and done. A take-away box, which sells for about 50 cents, is enough for lunch one day and breakfast the next.

At a sit-down restaurant like Will Long (where a meal runs about $2.50, including soup and Coke) and at least one of the canteens on campus, dishes are served en casserole – meat and vegetables on a bed of rice, which tastes best when it slightly burns onto the dish to form a crisp browned crust. The canteens also serve cafeteria-style, and while most of what I’ve sampled is delicious, I’ve learned to be careful. On my first pass through the line last week, I spotted a dish that, in the low light and without my glasses, looked just like my friend Ruth’s stir-fry of julienned lamb with scallions. I pointed, and the server dished up a generous portion. I noticed that one piece of meat hadn’t been cut all the way through; three pieces were still attached at one end. As I carried my tray into the light, I discovered they were all that way – because they were chicken feet.

The Sunday before classes started, Pam and I were invited to lunch with the family of a university administrator we met in New York, where she is spending a year doing postgraduate work. Her husband, who does not speak English, took us to a hotel in downtown Xiangtan with their 13-year-old son and a college-age niece and nephew, who do. Since of course we could not read the menu, they started out by asking us what we like; I ventured that I generally love what the Chinese do with beef, but we agreed we would trust them. Our host took over, ordering a long string of dishes, and then, as the meal progressed, even more. First course: Peking duck, crisp-skinned and golden, head right there on the platter staring at us, accompanied as always by thin pancakes and scallions and plum sauce. One vegetable dish after another, the standout being sautéed celery with toasted macadamia nuts. Soup with tiny clams in their shells and, I’m told, eel. Two kinds of dumpling: one filled with whole shrimp, and smaller, sweeter ones that were the traditional dish for the day, the last of the two-week New Year celebration. As the centerpiece, that beef dish I had requested, but like none I’d ever seen in a Chinese restaurant: a long oval platter of incredibly tender sliced beef in a brown sauce, garnished with bright green, mild-tasting broccoli, and the shank bone placed proudly beside it. Beef with broccoli – which I explained was a very popular Chinese dish in America – was never like this. “Do you need rice?” the nephew asked politely near the end of the meal. No one did.

Today I’ve just come from an English-speaking lunch with some graduate students: home-cured bacon to die for (think French lardons); eggs scrambled with tomatoes; spicy chicken and tofu; a winter soup of radishes and ribs; and, to top it off, a hotpot of fish soup, to which greens and delicate long-stemmed mushrooms were added for quick-cooking throughout the meal. On the way home, I stopped at Restaurant Row for something to take home for dinner later or breakfast, if there was any left by then. (At last! A place where no one thinks I’m eccentric because I like Chinese food for breakfast.) The fried rice man wasn’t there today; someone else was making pizza-like pancakes at his station. I went to his competitor, a woman who fries the rice on a flat grill. It’s very good but somehow lacks the je ne sais quoi of the cart down the street.

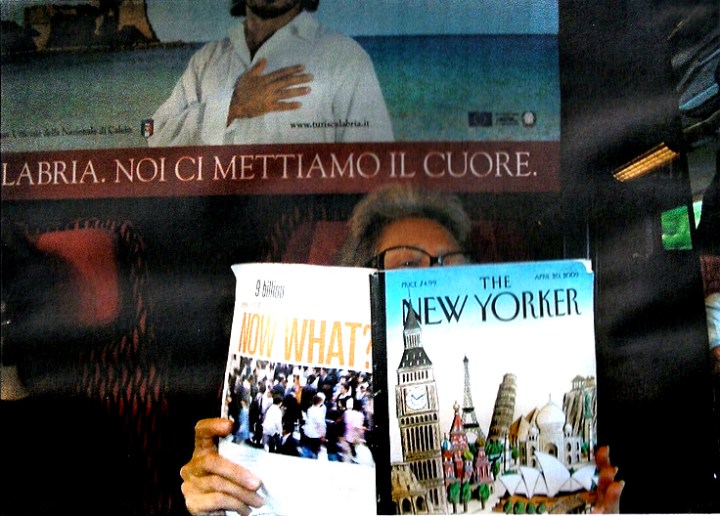

So far, despite the produce market right around the corner, I’ve had no temptation to cook for myself; why bother, a New Yorker thinks, when all this is right outside and sells for next to nothing by our standards? In previous incarnations I did a fair amount of Chinese cooking, mainly when living in places where there were no passable Chinese restaurants. In Roanoke, besides the Beef Black Pepper Spaghetti, I mastered moo goo gai pan, again from a newspaper recipe. Happily, there is no moo goo gai pan in sight in Xiangtan.